Big Learnings in a Tiny House: A Therapeutic Approach to Project-Based Learning

When we started the 2019 school year, we were still in a pilot program for just one child, developing the basis for our ground-breaking approach to therapeutic programming for twice exceptional kids. The task before us was a daunting one: how to replace what had become a full-on trauma reaction to math with at least a willingness to take some math learning risks?

We brought these emotional/trauma and curricular goals together in designing our first broad-scale project-based learning endeavor for the year. Looking across his profile of weaknesses and strengths, we saw that his executive function challenges interfered with traditional, lecture-style instructional techniques but that he was a natural-born problem solver. And we saw that his insistence that he was “horrible” at math might match to the long history of struggles to grasp basic math facts — but that it was utterly at odds with the extraordinarily complex and flexible rhythms he created as a self-taught drummer.

We found our answer by adapting a classic project-based learning project: to design and build the model for a “tiny house.” Here’s how we did it:

Math curriculum standards were unbundled into component cognitive skills and mathematical concepts, and then arranged in a new sequence that gradually scaffolded from his starting baseline skills to acquire the new skills, without regard to traditional curriculum sequences.

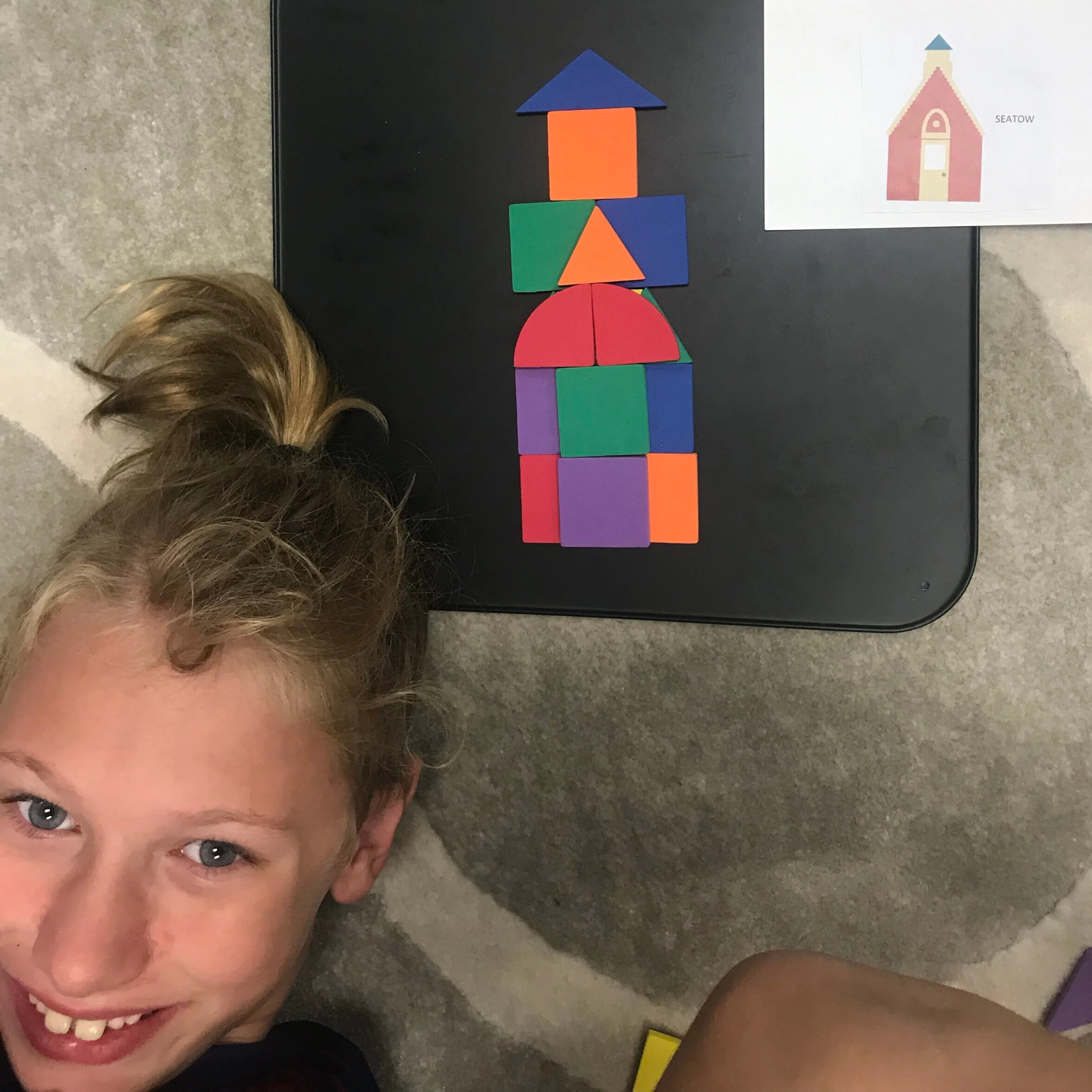

Manipulatives and scale drawings were used to design houses and floor plans, creating authentic course materials for teaching the concepts of area, perimeter, volume, measurement, scale and 2D-3D relationships, as well as reviewing basic math facts.

Measurement, scale, area and perimeter all came together on a field work trip to Captain’s Cove: a small pier filled with true, “tiny house” shops. Measuring the outside to calculate each one’s true size quickly turned into a confidence-boosting community social skills event, as each of the shopkeepers came out to hear our budding young architect’s verdict. One step inside made the realities of “100 square feet” visceral in a way that no workbook ever could!

Field work was used to emphasize the real world applications of the mathematical and design content we were learning. A “shape safari” trip through the community provided the opportunity to assimilate how two dimensional objects combine into three dimensional spaces.

Academic anxieties were reduced by combining math curricular standards, which we knew would trigger his math anxieties, with science standards we knew he felt confident, by adding units on electricity and alternative energy sources, and the impact of architects’ decisions on the world around them.

Field work and hands-on projects were added to challenge the notion that a house had to be a rectangle, building flexible thinking skills as well as visual-spatial ones, while providing opportunities to build community-based connection and social skills.

Executive function needs were incorporated into all aspects of the project, including scaffolded project management support and instruction in the skills needed to independently pursue areas of particular interest that can be used for a lifetime of self-directed learning.

We knew that memory and recall skills would be challenged by the long scope of our project and its many component parts, so we created a photo board capturing different stages in the process and the field work trips we took, using the photographs to help keep the lessons discussed there current in our working memories—like this image of how we’d calculated area from the measurements we took of each “tiny house”-sized shop.

Once our deep dive into the math and science parameters of the tiny house project were in place, we introduced our pupil to his real world client, and tasked him with integrating all he had learned by designing and building a model for a tiny house designed to best meet her needs. Ordinarily, these project parameters would have been introduced at the outset of the project-based learning process, however in our case we knew that this would overwhelm our pupil’s current executive function skills and increase anxiety levels in a way that would likely interfere with absorbing the curriculum content and skills.

Shortly after our client meeting, we expanded our program to include a new student — perfectly-time to shift from individual skill development to leverage the shared design task as a way to build the pair’s social skills, as they learned to advocate for their ideas, listen to those of their peer’s and reach compromises that brought the two together.

As design decisions began to turn into model-building, we brought visual-spatial and fine motor skills into the project framework as well, through building sessions co-taught by our occupational therapist. Individual pieces of furniture and design elements were assigned to each child according to their baseline fine motor and visual skills, allowing us to naturally differentiate to give each child an appropriate level of both challenge and support, according to their needs.

Preparing for our client meeting allowed us to shift gears to focus on the language arts, organization, communication and social skills required for a face to face interview with our client. The requirements of working within a client’s design parameters rather than his own elevated the relevance of the project by tying it to a real world client. It also provided an organic opportunity to develop his flexible thinking and social skills, by requiring him to design for someone else’s priorities, personality and preferences rather than his own.

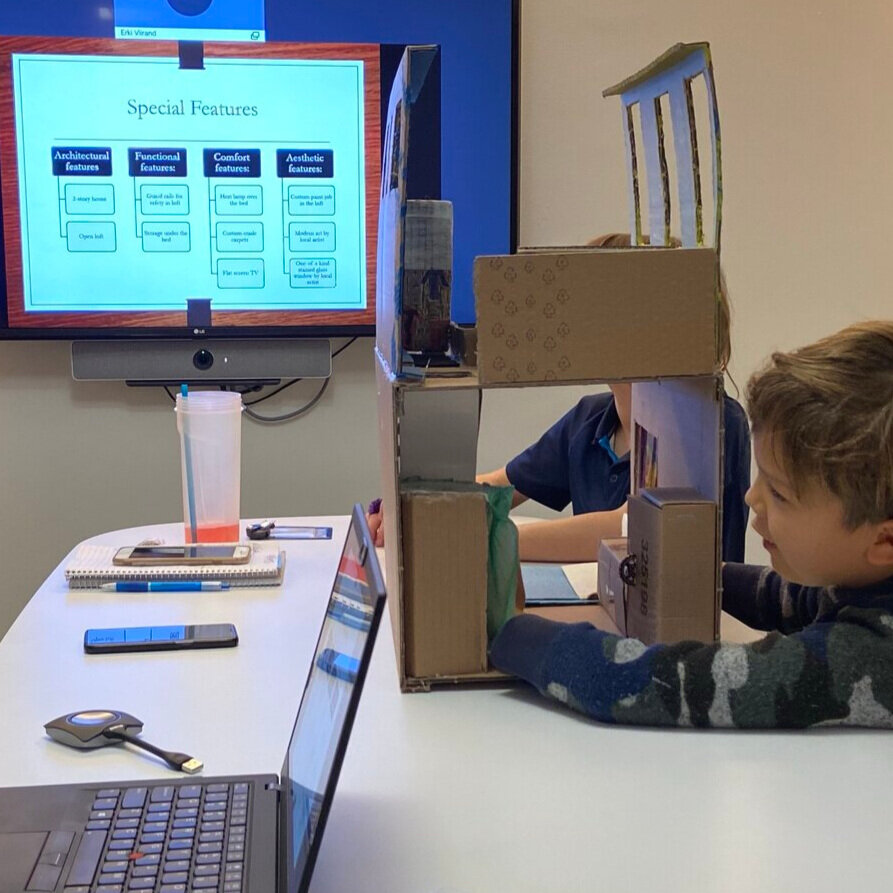

With our tiny house model in hand, we turned our attention to creating a professional presentation, using PowerPoint, and learning how graphic organizers can be used to organize and present information. We discussed the ways we communicate differently as professionals than we do in social settings, how client communications differ from social interactions with our peers, and how professionals take turns to ensure that all their team members had the opportunity to participate equally in the presentation — not things that comes naturally to eight and nine year old boys!

At last the big day arrived, and our small team traveled to meet the client at her office building. Proudly carrying their handmade model, the boys maturely took their places around a bright conference room table and beamed as they saw their presentation projected on the big screen. Each proceeded to explain a different portion of the project and why they had made the particular design decisions they had, using the sequence in the slides to organize their thoughts through an unscripted speech.

Pulling away from the client meeting, the boys chatted happily together, proud of the house they’d built, but more than that, proud of having acted as an expert. The potential this holds to empower children —especially ones who struggle with areas of learning, social and other differences—was summed up neatly in one of our young architects’ description of the day to his older brother: “I met with one of my clients today. It went very well.”

Our Tiny House project is but one example of how cross-discipline academic curriculum can be brought together with (and even in service of) therapeutic goals. At Cajal Academy, we are building on the flexible, project-based learning framework to support our integrated therapeutic and academic programming. Co-taught classrooms bring our clinical staff into the classroom, while our kinesthetic and self-regulation curricula bring our academic content into therapeutic settings. By taking the silos down and viewing our therapeutic work not as “related services” but as essential to the work itself, we are creating an instructional system that is as integrated as our students’ life-lived experiences.

We believe this is the right approach for all students, but especially for twice exceptional students, who have both high intellectual gifts and an area of social, emotional, learning or regulatory difference. For these kids, intellectual challenge is often essential to their emotional health, and this in turn requires removing the learning, social, emotional and regulatory challenges that threaten to stand in their way. Academic challenge and therapeutic support are therefore inseparable. Click here to find out more about how we are innovating on the project-based learning framework to provide the integrated healing and growth that these students need.

Students have an early dismissal on the day following most 3-day weekends and breaks, to enable them to ease back into school, recover from the fatigue of travel, etc. We plan required staff professional development and planning activities to coincide with these days. This is a mandatory attendance day, as we have found that it serves an important therapeutic value.

Come find out what’s possible when you switch to neuroscience-based education, and learn about our ground-breaking method for reducing or removing learning disabilities! We’ll be giving a tour of our historic facility, a “teach in” with our visionary Head of School on the neuroscience behind our program, and an overview of our very unique program and how we use that science to create transformative student growth. RSVP to join us in-person or online!