A skills-based approach to identifying what problems a child needs our help to solve

Finding the right solution starts with identifying what problem this child needs our help to solve.

At Cajal Academy, all programming decisions are made based on an iterative, three-step process of identifying what problem this child needs our help to solve, what levers we have available to “move the needle” and how we can give the child agency over this process to facilitate their independence.

The first step in this process is in many ways the most important, because if we don’t start by identifying the correct problem, we are unlikely to fashion the correct solution. This requires that we get behind the diagnostic labels that describe what a child’s challenges look like but not what drives them.

Our ground-breaking Neuro- and Trauma-Informed Approach gets beyond these labels through a research-backed methodology that reveals how the relative mix of strengths and weaknesses in their neuropsychological and neurophysiological profiles impacts their learning and social-emotional experiences: understandings that lead to actionable insights we can use to reduce or remove those challenges and not just the barriers they create.

This is a significant break-through that could revolutionize the field of education and implementation of the IDEA, by shifting from accommodating the diagnoses in a child’s profile to altering that profile so that fewer accommodations are required. This approach transforms children’s academic outcomes and quality of life, while reducing the costs to their family or school district of supporting their needs.

Start your child’s application today to find out how your child can benefit from this approach, or scroll down to learn more about our ground-breaking approach to assessing student needs.

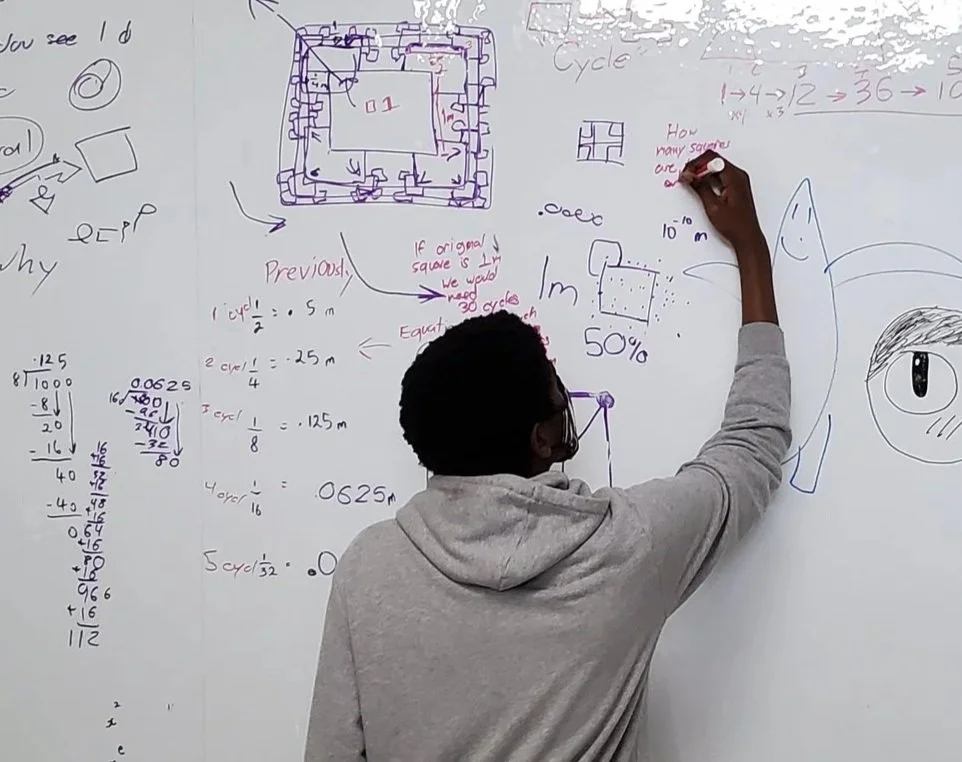

Re-understanding the things we ask a child to do reveals insights we can use to improve their ability to do them

At the heart of our program is a paradigm shift in how we understand children’s learning and social experiences and behaviors. Our Neuro- and Trauma-Informed Approach recognizes that each task we perform requires that we employ a mix of neurocognitive and neurophysiologic “splinter skills” simultaneously. Thus, a child’s performance on a given task will be impacted by their relative levels of strengths and weaknesses across the myriad “splinter skills” that go into performing that task. For students who have large gaps within their neuropsychological profile (as is the case for many exceptionally bright kids), this undermines their ability to predict which tasks will be easy or hard, generating experiences of academic or school-based trauma. Additionally, a child’s ability to access those skills in a given moment can be altered by a range of hidden, neurophysiologic events, thus further reducing the child’s ability to predict (or gain agency over) how they will fare in a given scenario. The net result is that many children have seemingly arbitrary experiences of success or fail.

Turning this around, if we can build up a child’s capacity to perform cognitive and physiological skills that are required for a range of learning, social and emotional experiences, then we can make meaningful improvements in their life-lived experiences. This is a fundamental principle behind Cajal Academy’s approach, and one that makes us meaningfully different from other special education schools.

Moving children forward starts with setting aside the labels that describe what their challenges look like

Realizing this opportunity requires that we dig behind labels like “ADHD” and “ASD” to identify at a very granular level the specific neurocognitive and neurophysiological skills that drive them. These diagnoses are made based on a child’s clinical presentation, but they don’t tell us why the child presents as they do. For example, a child may meet the diagnostic criteria for ADHD because they are struggling with a language processing disorder, anxiety or depression—or because they have an actual problem with their attentional system (in which case ADHD medication may actually be helpful to them). Needless to say, one would solve a language disorder very differently than one would treat anxiety—so knowing what problem is driving the presentation is essential to addressing the problem and not just treating the symptoms.

These cross-cutting skills come together in different combinations for different tasks, and a given child may be at very different ends of the bell curve with respect to one skill than they are with respect to another. So how successful a student will be at a given activity depends on how well that task matches to their current skill level with respect to each of the skills required to perform it. Thus, we can improve not only their academic experience but the quality of their life-lived experiences if we identify those low-lying skills that are holding a child back across multiple spheres and then work to build up their capacity to perform that specific skill.

We take a deep dive into the data to identify cross-cutting skill inefficiencies that are undermining their learning, social-emotional and life-lived experiences

Our research-backed methodology for identifying children’s needs begins with a deep dive into the learning, social, emotional, medical, sensory, executive function, auditory processing and other elements that influence how this child experiences the world. This work starts in the admissions process, as Director of Research and clinical neuropsychologist Steven Mattis, PhD, ABPP and other members of our clinical team look across the data in the child’s prior evaluations to identify those cross-cutting strengths a child is relying on, and also core cognitive and neurological deficits that may be manifesting across multiple, seemingly unrelated areas utilizing connections identified in peer-reviewed scientific literature and through our own evidence-based approach. This examination is integrated across learning, social, emotional and self-regulation spheres, with a goal of arming the child with strategies that are just as integrated as are their life-lived experiences.

For example, a child who has difficulty intuitively figuring out which of many details is the most relevant will have a difficult time trying to structure new information so that they can efficiently categorize and store it in their memory. This in turn may affect their abilities to efficiently recall and work with math formulas, spelling rules, history facts and even social feedback. For educators, this creates a patchwork quilt of special education accommodations and services. For the child, it can lead to a generalized feeling of being overwhelmed and less “smart” than their peers who may be quick to recall facts but may have lower analytical and/or creative thinking skills for how they work with them.

However, once we understand that in fact these several challenges are all stemming from a single low-lying skill, it becomes apparent that rather than “playing whack-a-mole” with a raft of individual academic and social challenges, we can give the child greater leverage across a range of issues if we focus instead on building up those cross-cutting skills that are impacting their performance across multiple individual areas. We call these skills our “Domino One’s,” because like the first domino in a maze, these are the skills that when addressed, can create the biggest improvement for the child.

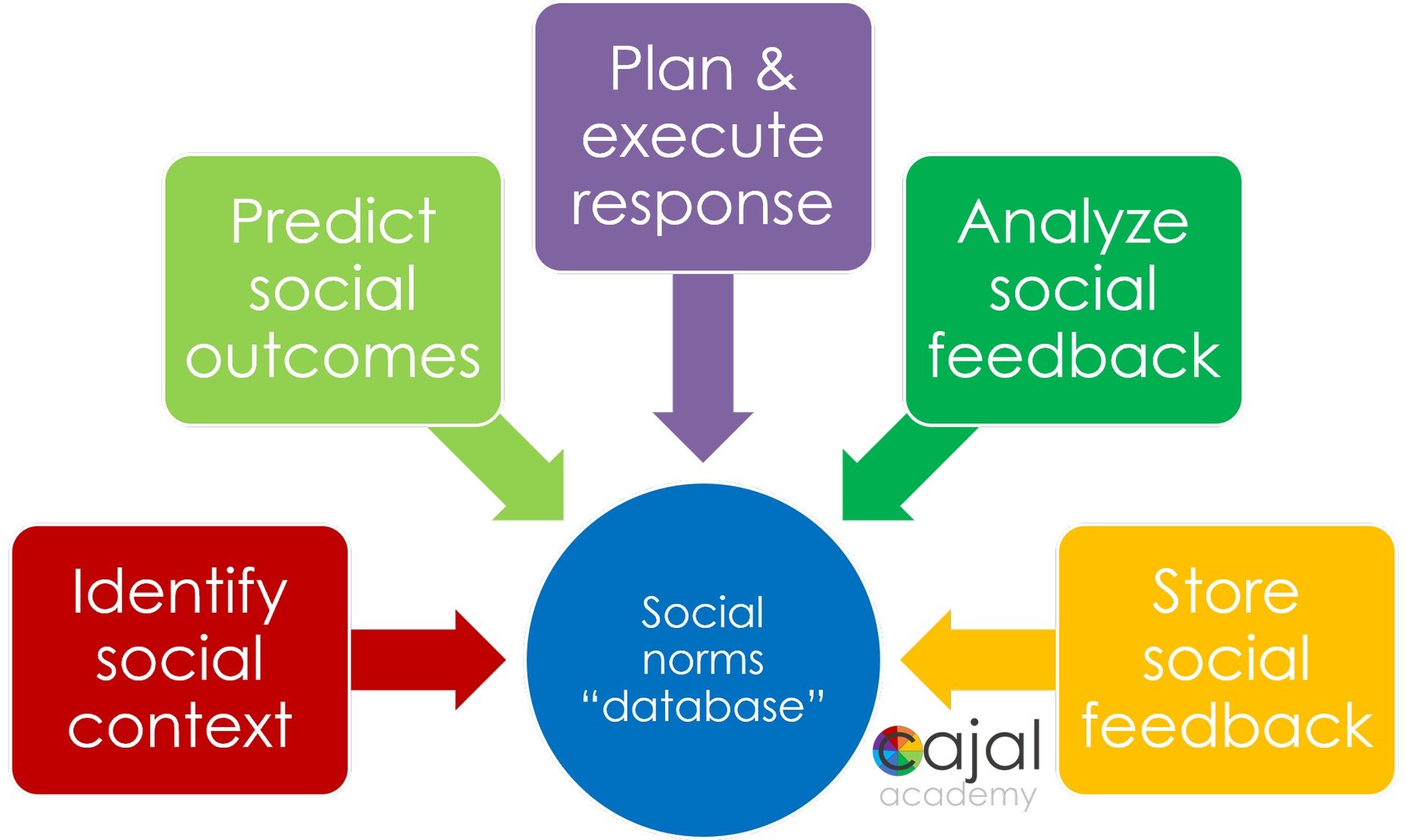

We take the same data-driven approach to understanding children’s social challenges as well. This approach recognizes that scientifically, not all behavior is functional, so we need a different approach to analyzing it than the Functional Behavioral Analyses used in ABA programs. This lens highlights those skills that we should prioritize through our Neuroplasticity Interventions, puts children, teachers and parents on the same side and gives them agency over moving the child forward. Critically, by teaching the child the science behind these connections between the child’s neurocognitive and neurophysiological skills on the one hand and their social and life-lived experiences on the other, we give them the knowledge they need to acknowledge and even forgive themselves for the areas where they are still working to grow.

Breaking the cycle of trauma for students with complex profiles

It is important to be mindful as we assess student needs that children’s life-lived experiences are (obviously) complex, and interactions between their learning and social-emotional needs will often be exponential rather than additive. For students with complex profiles, like many of the students we serve at Cajal, school and daily life-lived experiences may seem like an arbitrary and confusing mix of disproportionate moments of success and failure that often even their parents and teachers are unable to predict. Thus, a student may soar ahead on one occasion and experience a complete ‘fail’ on another seemingly identical task.

As students are repeatedly confronted with unexpected experiences of failure, it can act as an internal trigger for school-based trauma, triggering their “freeze-fight-flight” survival mechanisms and with them neurophysiological reactions that undermine access to their neurocognitive skills—thus perpetuating the cycle. This causes many students to become hypervigilant to the prospect of failure, leading to task avoidance or even school refusal in exceptionally bright children for whom school should instead be an intellectual playground. This in turn leads many children’s learning and/or neurophysiological difficulties to be misinterpreted as behavioral ones, when in fact the social-emotional difficulties are not a cause but a symptom. Where the behaviors in fact represent a trauma response, as is often the case for twice exceptional students, we must relieve the underlying trauma trigger (in this case, the skill disconnects) to address them; ABA and other behavior management techniques are not effective for this purpose and often have paradoxical effects.

Turning Insights into Growth

Developing the Student Growth Catalyst: an inter-disciplinary clinical program that reduces or removes learning and social-emotional challenges by enhancing the splinter skills that drive them

Armed with this scientific understanding of how the child’s skills profile, academic and social-emotional experiences intersect, we create comprehensive programs, called Student Growth Catalysts, that connect the dots between them and move the child forward on a holistic basis. Like a student’s IEP in public school settings, this program incorporates a mixture of services by licensed therapists, accommodations and academic differentiation, but unlike an IEP, each student’s Catalyst provides a roadmap for how to reduce or even remove those challenges, through a mix of traditional and Cajal-exclusive approaches, applying the well-established principle of neuroplasticity. Find out more about our Catalyst Method and how we develop individual student programs.