Assessing Social Needs

“Our aim is to empower children with the knowledge and the tools they need to understand and direct their own actions, including the complex drivers that go into them. ”

Improving Social-Emotional Outcomes Starts with Understanding the “Why” Behind a Child’s Social Difficulties

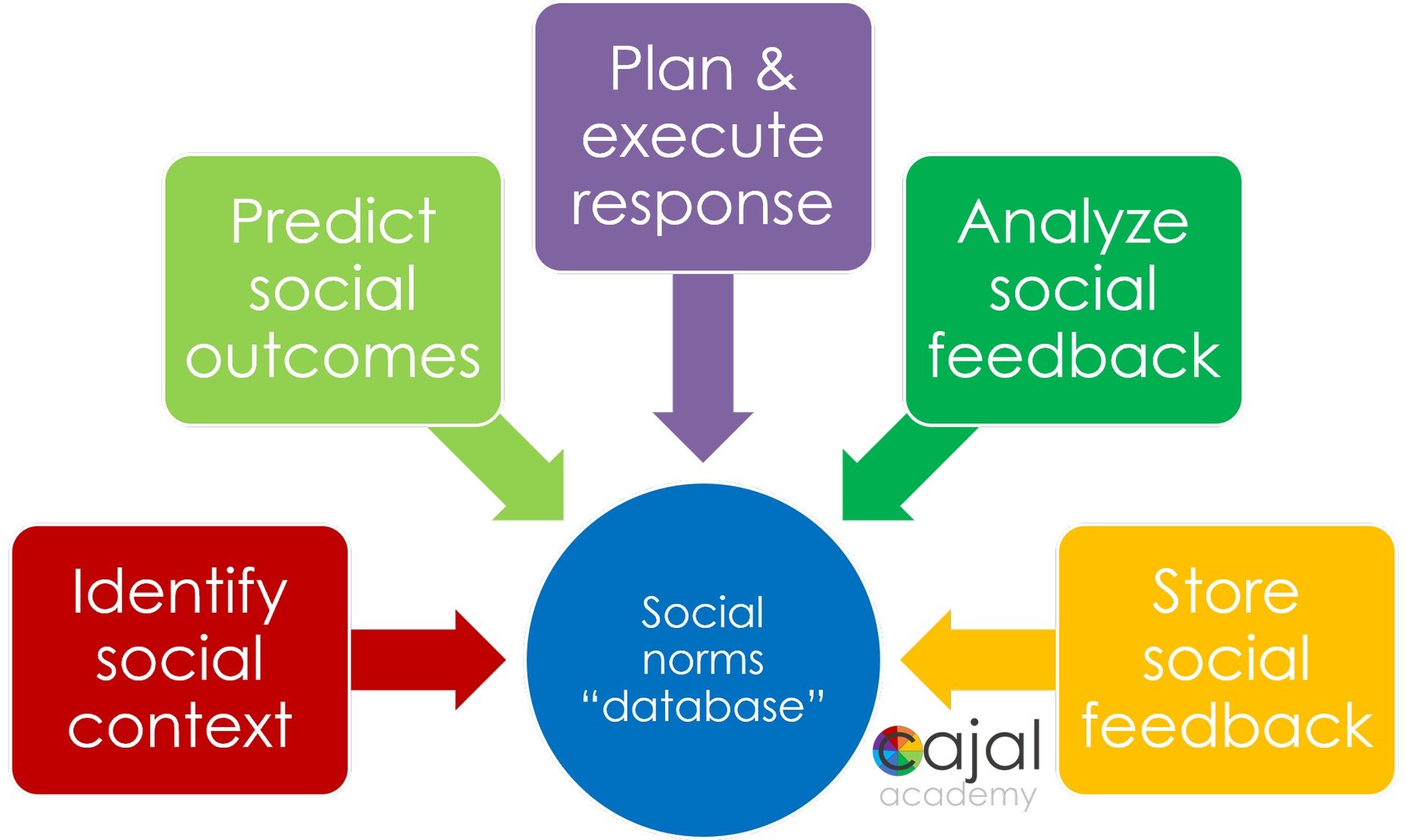

Social interactions are inherently complex . One must properly understand and interpret the environment, pick up nuances of how this setting differs from other ones, call upon one’s (hopefully accurate) database of prior social experiences, make a correct prediction about how others might respond to one action versus another, manage social anxieties and other dysregulating factors that undermine our judgment and control the impulse to take unhelpful actions and instead execute on the best course identified—all in the blink of an eye.

Further, each of these functions requires that we employ a number of “splinter skills” in real time,” while bouncing this information against the database of social understandings that the child has developed in response to their (correct or incorrect) analysis of prior social interactions.

Social challenges can be caused by the same “splinter” skill deficiencies that influence learning experiences

The net result is that social interactions can be impaired by the same skills that may cause learning difficulties—but they are even more likely to be dismissed as “behavioral” or motivation issues.

We approach social challenges in the same way that we do academic ones: by analyzing the data in their neuropsychological and neurophysiological profiles to evaluate whether there are areas of relative deficiency that would be likely to contribute to their observed social difficulties. This includes a cross-disciplinary analysis of how a given child’s social, emotional, cognitive and neurophysiological profile might be affecting their behavior or ability to regulate their own actions and emotions within a given setting.

Improving children’s social-emotional outcomes requires that we set aside our own assumptions about why they do what they do

Our social-emotional programming starts from the premise that children’s behaviors are outward manifestations of how they experience the world—not necessarily an intentioned act calculated to avoid tasks or secure attention. Rather, we view aberrant behavioral moments as windows into the problems that a child needs our help to solve.

To give an example, it’s only logical that children who don’t intuitively pick up and properly interpret social rules are likely to be breaking them—yet there isn’t a strong awareness of this in our cultural or in our media. This becomes particularly problematic for the very bright cohort of kids that we serve, whose social cognition challenges are more likely to be interpreted as “behavior problems” by well-meaning but ill-informed teachers, coaches, parents and peers who mistakenly assume that these kids will “just get it” because of their high aptitude in other areas. This misses a key opportunity to address the problem—while adding shame to the confusion and anxiety a child may already be feeling about their social interactions.

Hidden neurophysiological events can have a big impact on a child’s outwardly-observable functioning

Looking deeper, neuropsychological research reveals that in fact, any number of factors can alter the function of the brain in ways that drive behaviors. For instance, a child with ADHD might be overwhelmed by a chaotic environment, leading them to run about the room despite firm instructions to be still. Similarly, a child who has experienced adverse childhood experiences (from the loss of a parent to the stress or even humiliation of struggling over “simple” tasks due to an undiagnosed learning difference) might suddenly be sent into a survival state by any number of idiosyncratic and seemingly unpredictable triggering events.

Current neuroscientific research also reveals that many children’s behaviors are also influenced by a range of neurophysiological factors. Some of these are observable, like maintaining our postural control or reacting to a particular type of sensory input. Others are not—for example, children who do not regulate body temperature well may be thrown into a state of rage if they become either too hot or too cold—a problem that can be solved with an ice pack or a blanket, respectively.

Unfortunately, the connections between children’s bodies and their behaviors are not yet well-integrated into our cultural understandings about children. From teachers to parenting, adults are taught that “behaviors” indicate our children’s intents, and respond to them accordingly. These social expectations are set based on what most children can easily do most of the time as of a given age, and consequences flow accordingly. In our example, well-meaning parents and caregivers are more likely to punish the child for “throwing a tantrum” or behaving in an “unexpected” manner than they are to hand over that ice pack.

Yet for kids whose neurological development is atypical, when we impose these expectations without training them in how to improve the neurological functioning required to meet those expectations in the moment, we instead lay increase the child’s shame over their inability to meet those expectations. This does nothing to prepare them to better respond the next time, and in fact makes it even harder for them to act appropriately the next time, by entrenching triggers for a freeze, fight or flight reaction that physiologically impairs their decision-making capacity.

Developing individualized Catalysts to propel students’ social-emotional growth

Once we have identified the specific challenges driving a child’s social difficulties, we create a personalized Catalyst to propel their social growth. Like a student’s IEP in public school settings, this program incorporates a mixture of services by licensed therapists, accommodations and academic differentiation, but unlike an IEP, each student’s Catalyst provides a roadmap for how to reduce or even remove those challenges, through a mix of traditional and Cajal-exclusive approaches, applying the well-established principle of neuroplasticity. Find out more about our Catalyst Method and how we develop individual student programs.

Depending on the cause of their social difficulties, this may include Neuroplasticity Interventions building up the neural network they need to perform a given cognitive skill such as making social inferences; targeted social cognition curriculum; coaching from our occupational therapist in how to monitor and manage the sensory components of social interactions; social pragmatics therapy with our speech and language pathologist and other components that target the specific nature of the social challenge that has been identified.

Find out more about how we address these common social difficulties with the links below, or read more about our Catalyst Method and individualized programs.

Social Skills Curriculum

Social Instruction for Sensory Kids

Addressing Social Learning Disabilities

Neurophysiological Dysregulation